Hosted by

Colour, Form and Space: Rietveld Schrãder House challenging the future

Synopsis

The Rietveld Schrãder House in Utrecht was designed in 1924 by Gerrit Thomas Rietveld (1888-1964) for Mrs Truus Schrãder- Schräder (1889-1985), as a home for her and her three young children. Mrs Schrãder had very decided ideas about the modern family, the upbringing of her children, and a corresponding way of living. She wanted a flexible house that would be able to evolve over time in tandem with the changing needs of her family. Known and celebrated as the architectural expression of the ideology and design ideas of the De Stijl movement, the house is just as much the expression of the personal attitude to life and wishes of the client who commissioned it. In Rietveld, Mrs Schrãder felt she had found the ideal interpreter of her modern ideas.

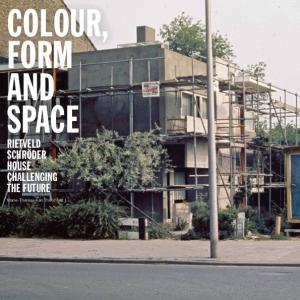

Mrs Schrãder lived in the house until her death in 1985, during which time it underwent several changes and alterations. By the 1960s the house was showing the effects of inadequate maintenance and the need for a comprehensive restoration became increasingly urgent. In 1974 work began on the restoration of the exterior. The interior followed after Mrs Schrãder’s death. Both restorations were carried out by the architect Bertus Mulder (b. 1929), who had worked with Rietveld in the early 1960s and knew his body of work better than anyone. In his restorations, Mulder opted to return the house as much as possible to its original condition, whereby the re-establishment of the original concept was considered more important than presenting or respecting the history of the house and its occupancy. Since the restorations the house is once more a shining manifesto of De Stijl and modernist living. Few realize that this is also one of the first examples of a restored modern heritage building. The Rietveld Schrãder House is also a milestone in the history of modern heritage restoration and a manifesto for the concern for modern heritage in the Netherlands.

In 2009, Bertus Mulder gave a personal account of the restorations of the house in the book Het Rietveld Schrãderhuis. He had already prepared a similar overview for the dossier in support of the UNESCO World Heritage nomination. Various reports and memoranda are also to be found in the Bertus Mulder archive. Owing to the restoration architect’s advancing years, the opportunities to draw on his memories in conversations are gradually diminishing. It was the value of this form of historiography — oral history — that motivated this study, which was made possible by a Keeping It Modern Grant from The Getty Foundation (2015). The conversations yielded a wealth of information, which was then weighed against the 2009 publication, and more especially with the many archival sources, in an effort to bring a degree of objectivity to the history of these restorations. During our investigations more and more new documents and pictures came to light and these have contributed substantially to the end result.

The aim of this historical research was to reconstruct the ‘Bertus Mulder time period’. This involved examining the guiding principles, points of view, choices, and outcomes. Also considered were the respective roles of Truus Schrãder of the client who commissioned the restorations (the Stichting Rietveld Schrãder Huis / Rietveld Schrãder House Foundation), and of the heritage agencies. And, given that the house has been managed by the Centraal Museum and opened to the public as a museum house since the completion of the restorations in 1987, the museological decisions made during the restoration of the interior were also subjected to scrutiny.

In Rietveld’s design concept the materialization of the external and internal walls, in plasterwork and paintwork, were of crucial importance. In addition to the three-dimensional spatial composition of horizontal and vertical elements, and the interplay of inside and outside, open and closed, the Rietveld Schrãder House as a whole, from ground level to roof, from floor to ceiling, displays smoothly finished and painted surfaces. In restoring the original concept of the house, the finishing of those external and internal walls, the paintwork and the choice of colours, were therefore key considerations. This is why the first three chapters focus on the ideas and principles that informed the restoration of the inner and outer skin of the house. The crumbling of the internal plasterwork (2016) gave the research an unexpected twist and also led to a limited material survey of the wall finishes.

During the restorations, Mulder dismantled large areas of the inner and outer skin down to the structural shell. After which he ‘made a recreation of the Rietveld Schrãder House, together with Truus Schrãder and the advisers’. The architect is convinced that with this the last, definitive phase in the creation of the house was completed. This recreation of Rietveld’s work has added a new dimension to the history of the house. This is not only important from a historiographical perspective but also forms a new challenge for future restorations.

In the fourth chapter, the guiding principles of the furnishing of the museum house are placed within the context of the occupational history of the house. After the death of Truus Schrãder the interior of the Rietveld Schrãder House was restored in an ‘abstract manner’ in the spirit of the 1920s. But how can the supposedly all-important ‘domestic culture’ be represented if the museum house is not allowed to suggest that the occupant has just stepped outside?

Finally, one further aspect, which is set to become very important for the future use of the museum house, is addressed: the indoor climate. Today, almost a century after the house was built, the measurement of temperature and humidity, in relation to outdoor climate and visitors, ought to be an essential part of ensuring a sustainable future for the Rietveld Schrãder House as heritage building, as museum house and as collection object.